3.1 The Seven Village Stages that Existed in Hitachiomiya City

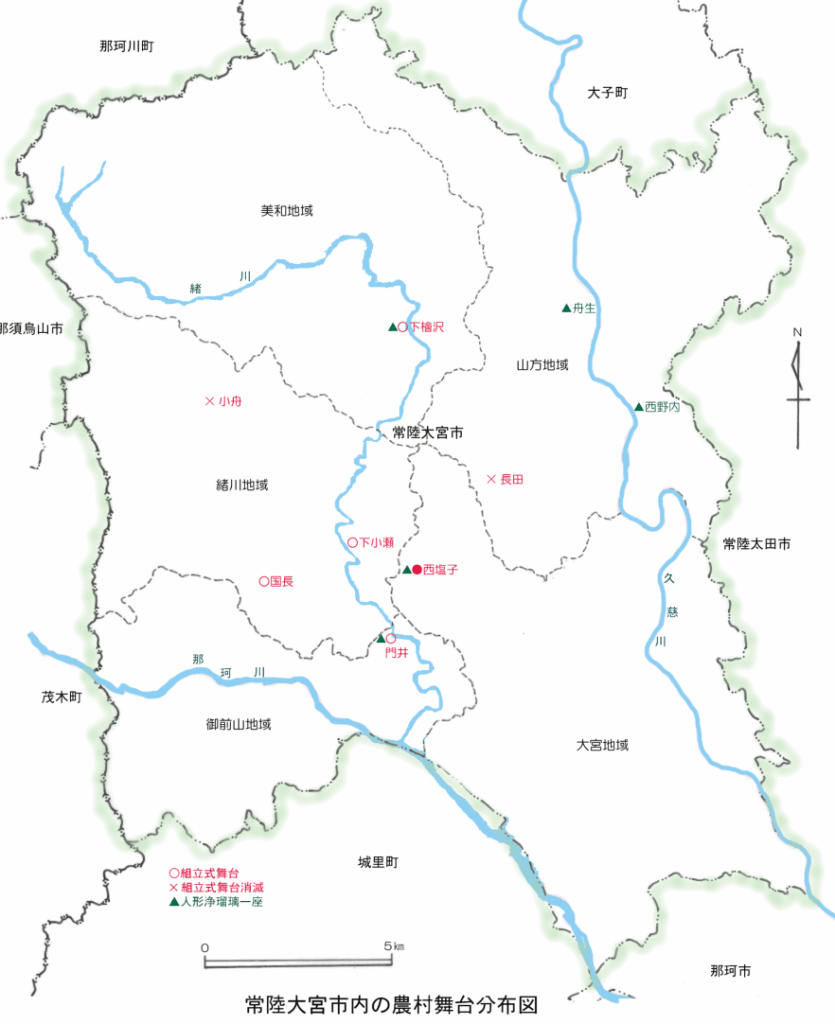

Prompted by the survey of “The Nishishiogo Revolving Stage,” verification work progressed throughout Hitachiomiya City. It is now known that seven stages, including Nishishiogo’s, existed across the city, all of which were assembly-type stages. Additionally, there were Ningyo Joruri (Puppet Theater) troupes (za) in two locations, which owned curtains and fusuma (scenery panels).

The seven stages were located in Osada(formerly Yamakata Town), Shimohizawa (formerly Miwa Village), Shimo-ose, Kuniosa, Kobune (formerly Ogawa Village), Kadoi (formerly Gozenyama Village), and Nishishiogo (formerly Omiya Town), existing in all of the former municipalities. However, looking closely, their distribution is uneven. The stages where props from the Edo period have been confirmed are Nishishiogo and the adjacent Shimo-ose and Kadoi (three locations). Stages presumed to be from a later period are distributed around them. This is only an estimation, but it seems that these three neighboring locations competed in building stages, and this influence gradually rippled out to the surrounding villages.

In Kobune, two large draw curtains (hikimaku) were reportedly lost after the war. It is said, “Without a curtain, there is no play,” and the stage props were distributed to those who wanted them and were scattered. It seems the Omaku (Grand Curtain) of a stage was an indispensable and important prop, more so than we might imagine. For such reasons, it is thought that the existence of a Konya (master dyer) in Shimo-ose, who reportedly trained in Oshu-Sendai and possessed the skill to dye a grand stage curtain, may have been deeply involved in the origin of the stages in this area.

3.2 The Scale and Structure of Nishishiogo’s Revolving Stage

Nishishiogo’s Revolving Stage is “Assembly-type”

Currently, Hitachiomiya City is the only place in Ibaraki Prefecture where village stages have been confirmed, and they are densely clustered. There are also assembly-type stages in the eastern part of Tochigi Prefecture, which corresponds to the upper reaches of the Naka River flowing through the city, and the influence of that culture is conceivable. However, it is not well understood why so many assembly-type stages were built in this area.

“The Nishishiogo Revolving Stage” is an assembly-type stage where only the flooring components, including the Hanamichi (stage walkway) and Mawari Butai (Revolving Stage), and the stage props are retained. The timber and bamboo used for the pillars and roof are cut down as needed and sold off after use. Taking advantage of this characteristic, the stage was also frequently rented out to other villages.

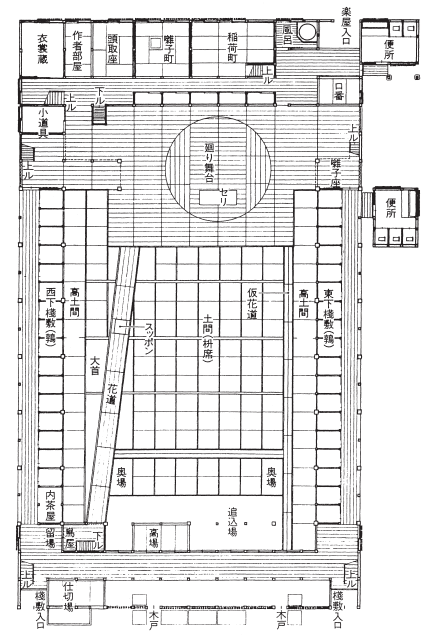

Stage Scale Adapted to the Site

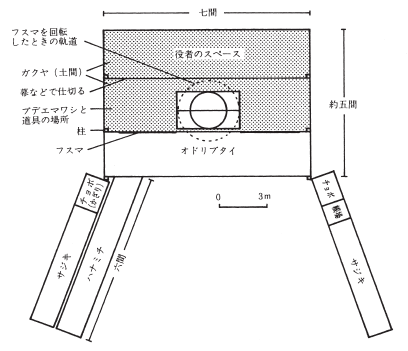

The stage can be assembled with a frontage ranging from four ken (approx. 7.3m) up to a maximum of seven ken (approx. 12.7m), one ken at a time, depending on the site. The Hanamichi can be assembled to a length of four or six ken. In the center of the stage rear, about one jo (approx. 3m) deep, the Mawari Butai—which is the origin of the stage’s name—is installed one step higher, with a frontage of two ken and a depth of eight shaku (approx. 2.4m). Behind it are the storage and dressing rooms.

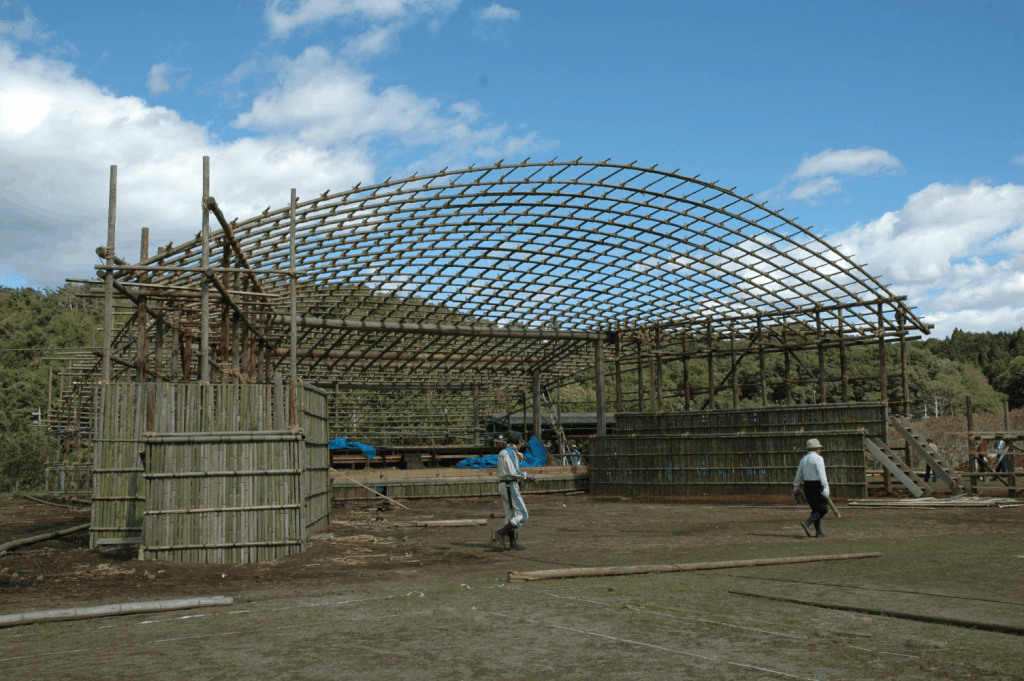

For the roof framework, Madake (Japanese timber bamboo), measuring five to seven ken in length, is assembled in a lattice pattern and tied with rope, then covered with Komo (woven straw mats). The roof over the fan-shaped seating area is designed to form a natural arch from the flex of the bamboo, which is installed in a flip-up manner. People called the foremost curve the Kagami and evaluated the beauty of this as the quality of that year’s stage.

Though “Assembly-type,” the Stage is Sufficiently Large

The term “assembly-type stage” strongly evokes an image of being temporary, and it is often assumed to be smaller and weaker than a permanent one. However, permanent stages built on the grounds of shrines are surprisingly small, with most having a frontage of four to five ken. The Nishishiogo stage, with a maximum frontage of seven ken and a Hanamichi of six ken, is actually larger. The Ichimura-za theater in Edo during the Bunka-Bunsei eras (early 19th century) is said to have had a stage frontage of about six and a half ken. Therefore, although it lacks a Seri (stage lift) or a Suppon (a Hanamichi lift), it can be called a magnificent and stately stage with sufficient size, even for an assembly-type.

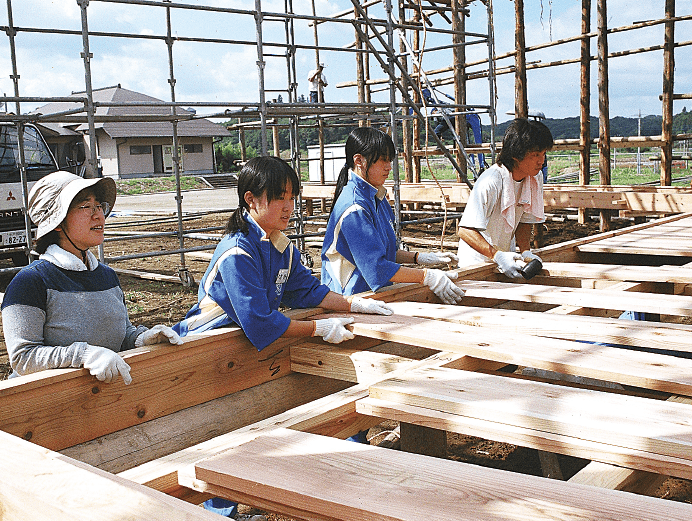

In the old days, they spent about a month in late autumn after the rice harvest, cutting timber and bamboo, and borrowing a field before the wheat was sown to assemble the stage. When the plays were over, they dismantled the stage, auctioned off the unused materials, and the entire village tilled the field before returning it to the landowner.

Currently, the wood used for pillars and posts is retained, but the bamboo for the roof is cut down for each assembly. It is assembled on the grounds of the community center in the adjacent Kita-Shiogo area with both the frontage and Hanamichi at six ken. When the Sajikiseki (box seats) are set up and the dressing rooms are built, the entire facility has a frontage and depth of about 20m, and the highest point of the roof is about 7m.

The Revolving Stage Evolves with the Times

We do not know what the stage looked like when it was first built, or when the flooring components stored in the warehouse were prepared. However, a koro (elder) born in 1894 (Meiji 27) said, “It seems the current stage, which was planed with a kanna (plane), was built because the actors disliked damaging their costumes.” He also stated that, as far as he could remember, the stage always had its existing Hanamichi and Mawari Butai.

However, the Mawari Butai, which the koro recalled being rotated by pushing iron bars in the Naraku (understage area), was at some point improved to an uwamawashi-shiki (top-rotated) system (see note). The stage has been modified according to the times. Even after its revival in 1997 (Heisei 9), deteriorated components and props are preserved as cultural properties, and we are actively replacing them with new components and props sized to fit the physique of modern people.

*Note: At the time of the 1991 (Heisei 3) survey, it was a system rotated by pulling fittings attached to the upper side of the turntable.

3.3 Stage Props and the Village Artisans

The Importance of “Props”

Although the stage frontage is on par with an Edo theater, the stage itself, with its framework of logs and bamboo covered in Komo mats, is by no means glamorous. To transform it into a Kabuki stage, an alternate space from the everyday, the props play a crucial role. Indeed, possessing these props was synonymous with “possessing a stage.”

A draw curtain (hikimaku) 3.3m high and 11.5m wide.

“Props” Were Handcrafted by Village Artisans

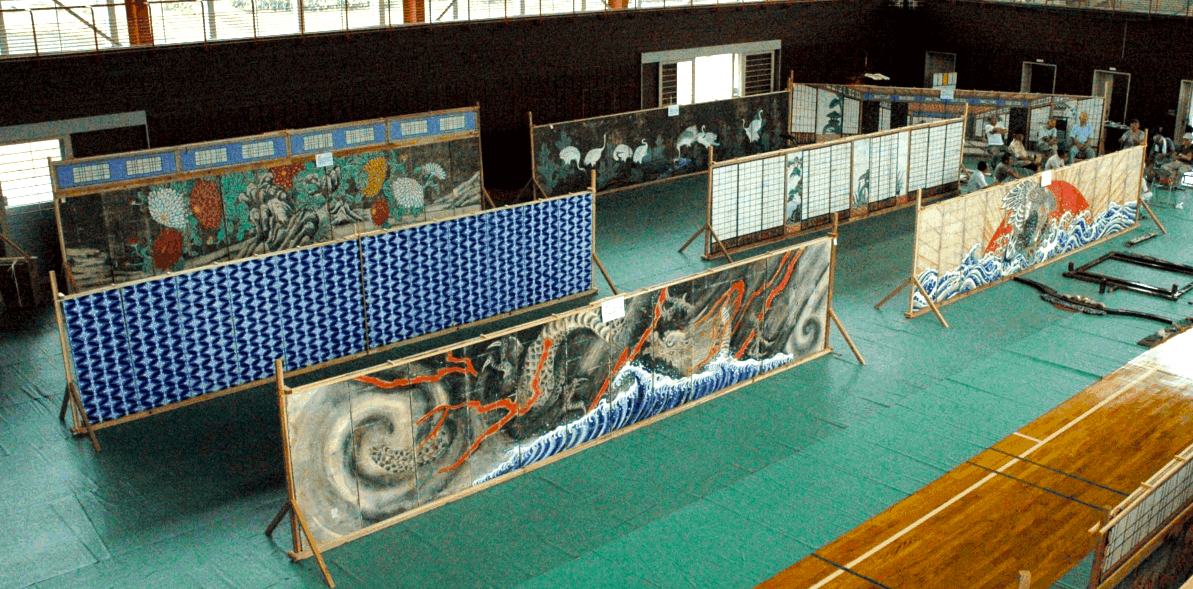

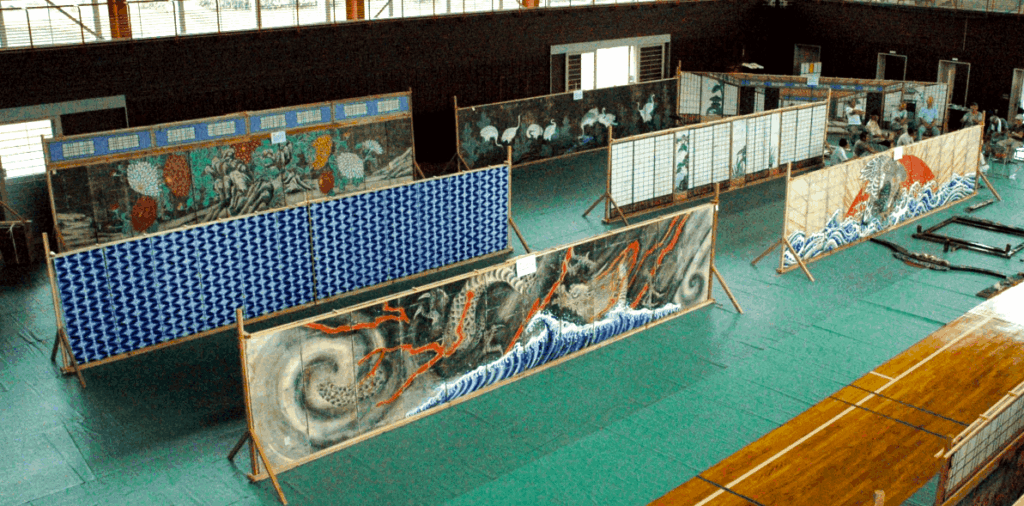

“The Nishishiogo Revolving Stage” retains over 60 large and small props, including the hon-yuka (chobo / narration platform), fusuma (scenery panels), ranma (transoms), and kekomi (risers) that form the stage background, as well as the Omaku (Grand Curtain) and Mizuhikimaku (stage border curtains). Among them, several props listed in the “Nakama Shodogu Hikaecho” (Bunsei era ledger) have been confirmed. Above all, the fusuma, made in sets of 12, were representative props, and how many sets a village owned was a source of pride. The elders used to call the fusuma “Budee” (a dialect word for “stage”).

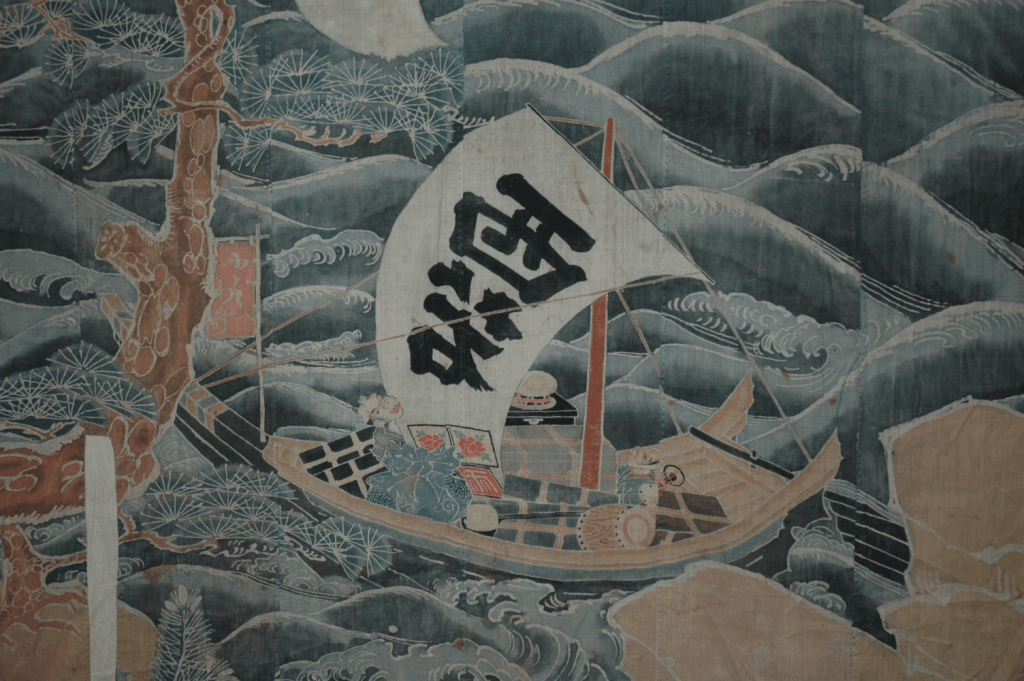

Carved hon-yuka decorate both wings of the stage. A Mizuhikimaku, using luxurious materials such as silk, brocade, velvet, and rasha (wool cloth), is hung above the stage. A magnificent Omaku, dyed with a design of the sun rising over a great sea of crashing waves, is drawn across the full frontage. Lanterns on the stage, Hanamichi, and Sajikiseki (box seats) glow, completing the gorgeous Kabuki stage. And surprisingly, many of these splendid props were not obtained from the market towns, such as the castle town, but were handcrafted by artisans living in neighboring villages.

The High Level of Rural Culture at the Time

There are two hon-yuka that adorn the tayu-za (narrator’s platform) for Joruri. One, from the Bunsei era, was made by Masakichi, a carpenter from Kamiose (now in the city). The other was made in 1889 (Meiji 22) in Torinoko by Kobayashi Heiemon, who was praised as a master of Torinoko carving. The Omaku, bearing the date Bunsei 3 (1820), was dyed by Mr. Nagayama, a Konya (master dyer) from the neighboring village of Shimo-ose (now in the city), on fabric that the people of Nishishiogo had cultivated, spun into thread, and woven themselves. The paintings on the fusuma are said to have been painted by Nozawa Hakka, a painter from Tatsunokuchi (in the city) who was active in the Meiji period, and background paintings by Yokoyama Otomatsu, a local from Nishishiogo, also remain. “The Nishishiogo Revolving Stage” thus teaches us about the high standard of rural culture at that time.