2.1 The History of Kabuki and Its Spread to Rural Areas

The first appearance of the name “Kabuki Odori (Kabuki Dance)” is in 1603 (Keicho 8). It is said that Izumo no Okuni, who originally performed “Yayako Odori” (a children’s dance) based on Furyu Odori (a genre of folk performance originally held to console the spirits of the dead), adopted the customs of the “Kabukimono” (eccentric performers or samurai) of the time and arranged them into a dance. This was a huge hit in Kyoto and received enthusiastic support. Performance troupes were formed one after another and traveled to the regions, and many troupes (za) performing Kabuki were also established in the regions, leading to a nationwide boom.

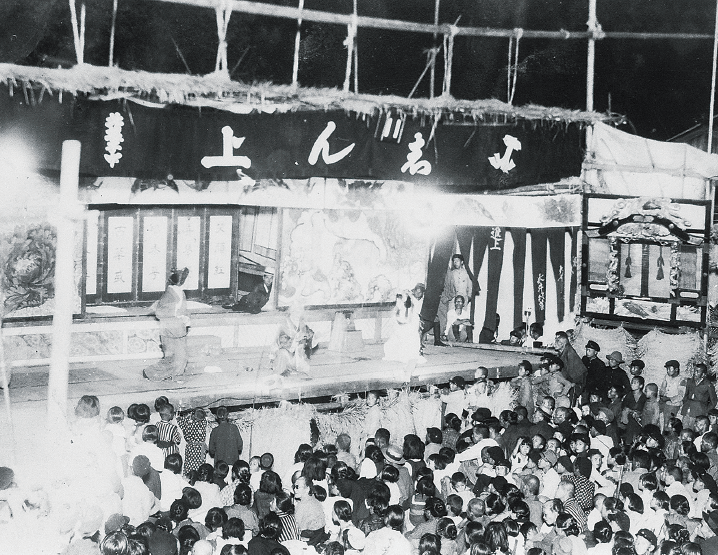

as entertainment at the Omiya Gion Festival

(c. 1950 / Showa 25).

| Year | Era | Event |

|---|---|---|

| 1603 | Keicho8 | Izumo no Okuni performs Kabuki Odori at Shijo-Kawara, Kyoto. |

| 1629 | Kan’ei6 | Onna Kabuki (Women’s Kabuki) is banned. |

| 1652 | Sho’o 1 | Wakashu Kabuki (Young Men’s Kabuki) is banned. |

| 1653 | Sho’o 2 | Kabuki is permitted to resume on the condition that actors shave their forelocks (to adopt the Yaro-gashira hairstyle) and perform Monomane Kyogen-zukushi (mimicry-focused plays). |

| 1667 | Kanbun7 | Dances are performed for the first time at the Tenno Festival in Karasuyama, Tochigi Prefecture. |

| 1678 | Enpo6 | The Mito Domain officially permits Kabuki performances in the castle town. |

However, as a result of repeated prohibitions by the shogunate for “corrupting public morals,” by the mid-17th century, it moved away from songs and dances that focused on sensual appeal. Instead, it took its current form of “Monomane Kyogen-zukushi” performed only by men—that is, theater as a dramatic art. It evolved from skits based on local customs into plays with a narrative structure, and this form also spread rapidly to the regions. In the Mito castle town, Kabuki performances were officially permitted as early as 1678 (Enpo 6).

After that, due to the influence of the Kyoho Reforms and the emergence of the genius playwright Chikamatsu Monzaemon, Kabuki’s popularity temporarily declined as Ningyo Joruri (Puppet Theater) gained favor. However, Kabuki evolved by incorporating programs and production techniques from Ningyo Joruri, and by devising new stage mechanisms such as the Mawari Butai (Revolving Stage).

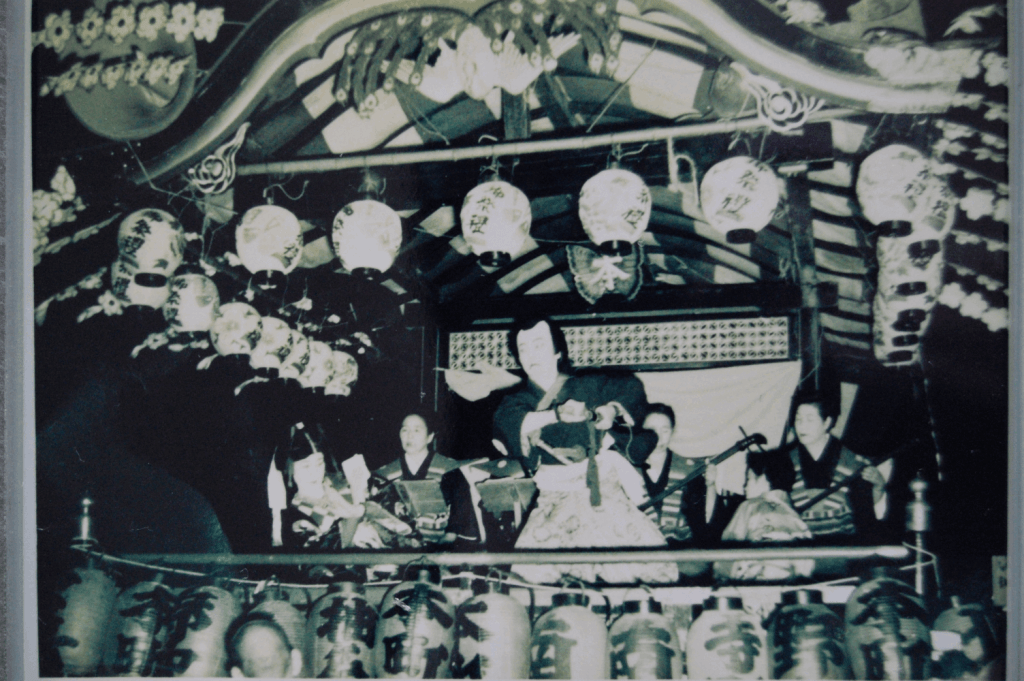

Then, in the 18th century, farmers were no longer satisfied with just waiting for and watching the Ningyo Joruri and Kabuki troupes that came to their villages; they began to perform the plays themselves on stage. On floats (yatai) and village stages, illuminated in the darkness by the light of lanterns, actors dressed in gorgeous costumes called Kira unfolded comedies and tragedies. This alternate space was a world of intoxication for both performers and spectators—truly the centerpiece of the festival. We today can easily understand why Kabuki spread so rapidly throughout the country.

2.2 Rural Kabuki and Village Stages

Even in the area of present-day Hitachiomiya City, which was a rural village in the Mito Domain in a remote part of the northern Kanto region, stage performances were held in the villages by 1751 (Horeki 1). This is written in the “Nengotome” (“Chronicle”) by Kono Ruhei, the Yamayokome (see note) of Kamiaiga Village.

Furthermore, in 1769 (Meiwa 6), Kabuki (written as “Odori” or “dance”) was dedicated by local children as festival entertainment at the In’yosan Shrine in the city’s Yamagata area. However, the rental fee for the costumes was prohibitively expensive and could not be paid, which sparked an incident that developed into a movement to dismiss the Yamayokome (see note). By this time, Kabuki was already so widespread among the populace that there were vendors who rented costumes to farmers.

*Note: A Yamayokome (Mountain Overseer) is equivalent to an Ojoya (Head Village Administrator) in other domains. They served under the Gun-bugyo (District Magistrate) and held the highest rank among village officials.

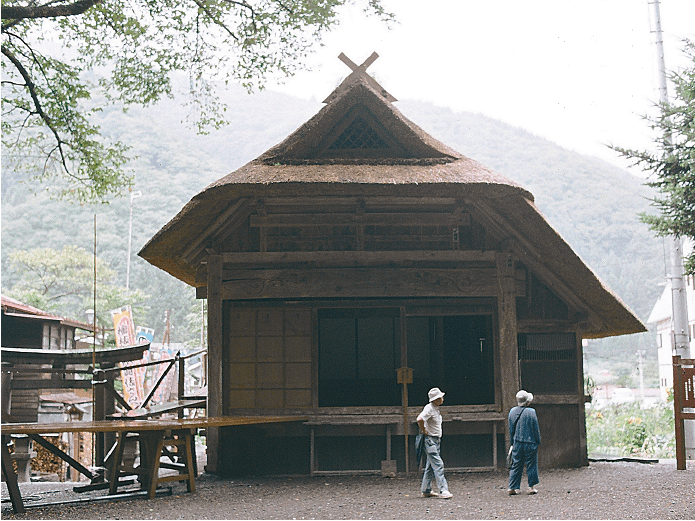

Following this trend, stages for Kabuki performances came to be built not only in regional cities but also in agricultural, mountain, and fishing villages nationwide. This trend continued until the early Showa period. A survey conducted in the Showa 40s (c. 1965–1974) confirmed over 2,000 village stages remaining in Japan. However, few were assembly-type stages; most were permanent stages.

2.3 Ningyo Joruri (Puppet Theater) and “The Nishishiogo Revolving Stage”

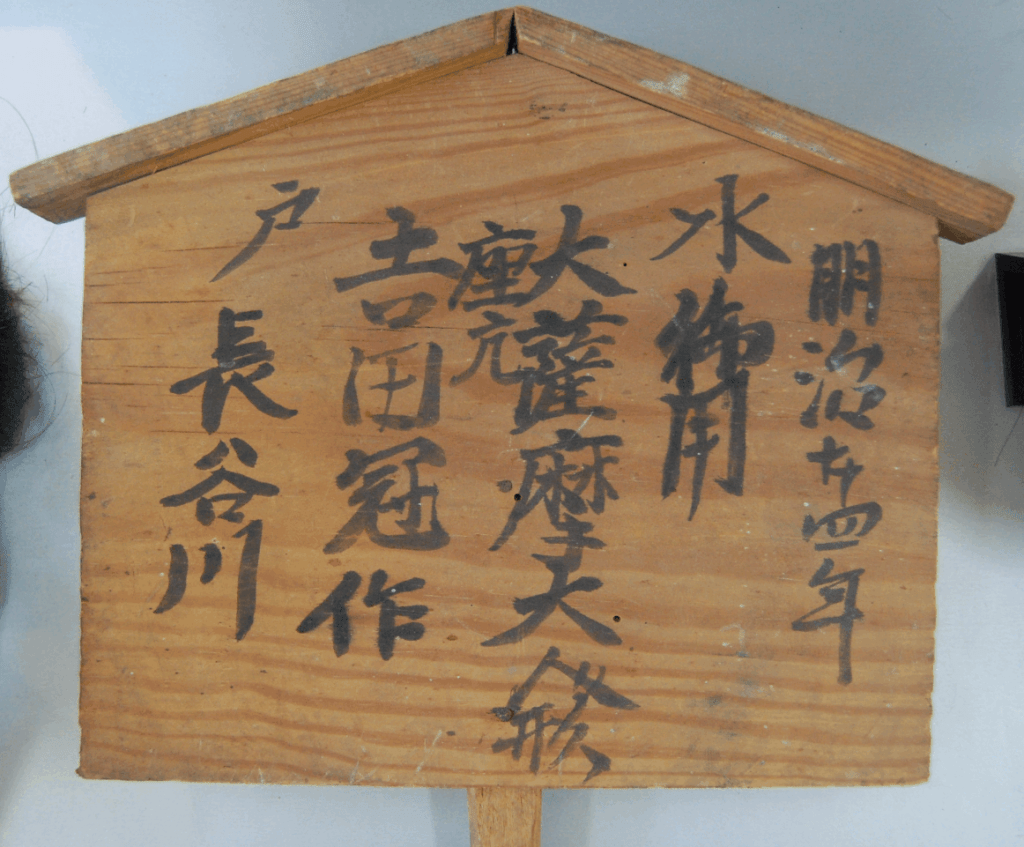

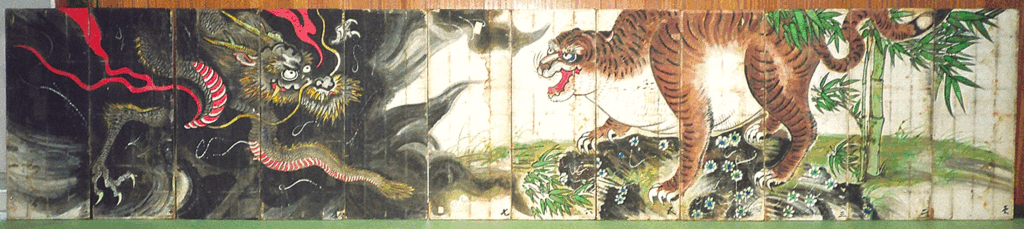

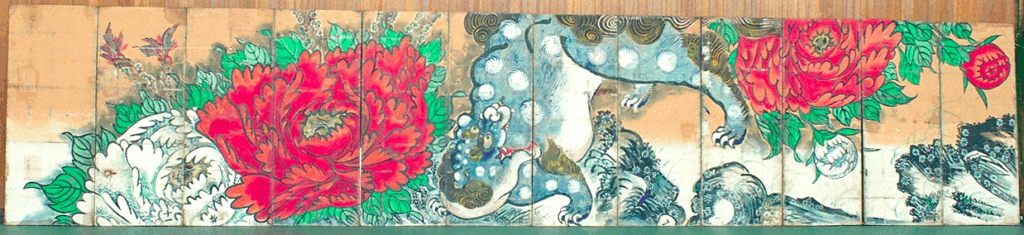

(Collection of the Hitachiomiya City Historical and Folklore Museum, Yamagata-kan)

According to the koro (elders knowledgeable in past events and traditions), Nishishiogo once had a Ningyo Joruri troupe. As if to prove this, puppet props such as kashira (heads) are listed in the “Nakama Shodogu Hikaecho” (a ledger from 1823(Bunsei 6).

In the Mito castle town, there was a Ningyo Joruri troupe called the Osatsuma-za. Tradition holds that it was given by Tokugawa Ieyasu to the first lord of the domain, Yorifusa, when he was still a young child. This troupe often held performances in the domain’s rural villages and also had a permanent playhouse in Mito’s Izumi-cho. It is said that due to the influence of this Osatsuma-za, Ningyo Joruri flourished within the Mito Domain, and there were also puppet troupes in Funyu and Nishinouchi within the city.

Since props from the late Edo period (Bunsei era) remain for “The Nishishiogo Revolving Stage,” it is thought that the stage was already being assembled around this time. Given the fact that they possessed puppet props during the same period, and that the size and design of the props called fusuma (scenery panels) are common to Ningyo Joruri props from distant Tokushima Prefecture, one might want to say that “The Nishishiogo Revolving Stage” was originally a Ningyo Joruri stage. However, the Omaku (Grand Curtain) made in 1820 (Bunsei 3) is six ken (approx. 11m) wide, which is too large for a puppet stage. We cannot be certain, but it may have been a stage designed to be usable for both Kabuki and Ningyo Joruri.

According to remaining records, the Ningyo Joruri props were sold off in 1901 (Meiji 34). It seems that Ningyo Joruri ceased to be performed in the early Meiji period. After that, on “The Nishishiogo Revolving Stage,” Kabuki performances, primarily by Kaishibai (performances by professional troupes), were held until 1945 (Showa 20).

2.4 How Performances Vitalized the Local Economy

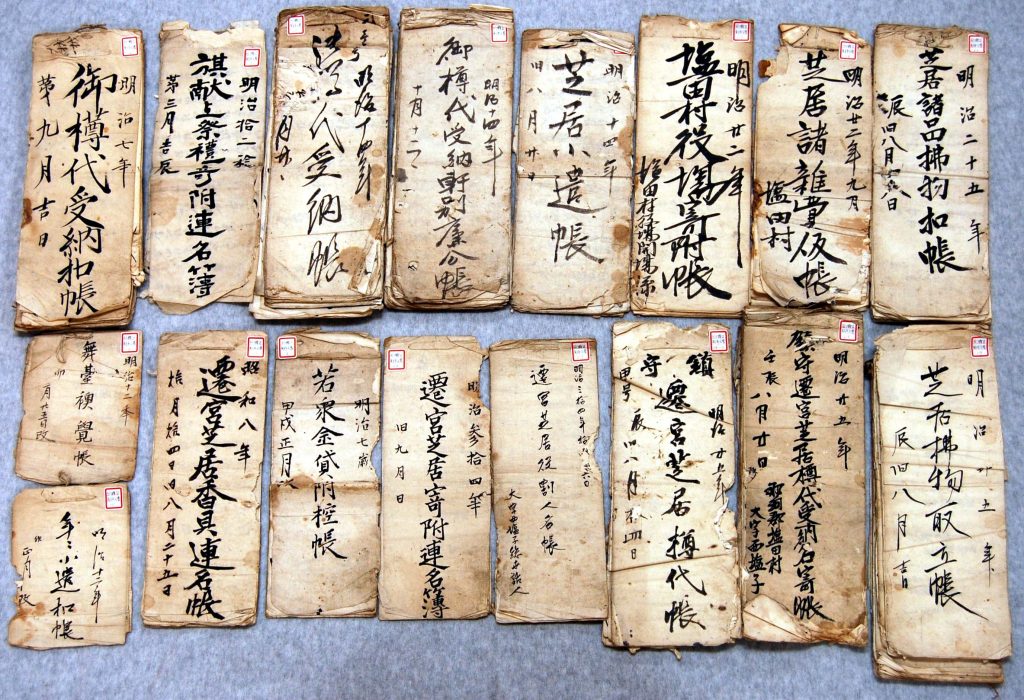

About 40 documents related to “The Nishishiogo Revolving Stage” remain. These historical materials, spanning about a century from 1823 (Bunsei 6) to 1933 (Showa 8), mainly concern the plays performed as entertainment for the Sengu (periodic rebuilding and transfer) of Haguro Kashima Shrine, the Chinju (local guardian shrine) of Nishishiogo. Reading these carefully reveals how much the plays cost and what methods were used to finance them.

The Sengu, held irregularly in conjunction with shrine repairs, was the village’s largest festival. The play performed at that time was called the “Oshibaya” (“Great Play”) and was always held for two nights. For festivals such as the storm-warding ceremony, which were mainly run by the youth group, they reportedly hired actors from nearby Iino (Mogi Town, Haga District, Tochigi Prefecture) for a single-night play. However, for the Oshibaya, it is said they “bought” (hired) expensive actors. For the last Sengu play, held in 1933 (Showa 8), they apparently hired a Kabuki troupe from Tokyo called the Matsubaza.

Looking at the Sengu play of 1901 (Meiji 34), for which the most documents remain, the total cost was just over 600 yen in the currency of the time. This is perhaps equivalent to about 8 million yen today. It is astonishing that a hamlet with only about 70 households held a festival that incurred such expenses in an era when cash income was scarce.

Let’s look at the breakdown of income. Notable items include the “Shohin Haraimono Dai,” which were proceeds from auctioning off everything from the timber and bamboo used for the stage to the lamps and paper waste after its disassembly, and the “Wakashukin” (youth group funds), which were savings from stage rental profits (this was used as capital for intra-village financing). But what is most noteworthy are the “Tarudai” (Cask Money) and “Ikki Tarudai” (Individual Cask Money), which accounted for about 40% of the income. This was goshugikin (celebratory money), or so-called “Hana,” brought by spectators. How many spectators could be gathered was the key to a successful performance.

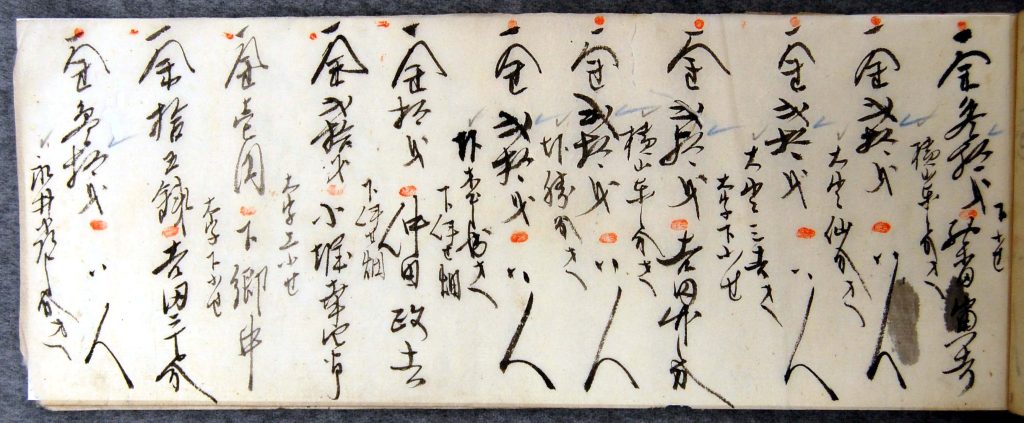

(Cask Money Receipt Ledger) / 1901 (Meiji 34).

Whereas the “Tarudai” was celebratory money given to the Nishishiogo district, the “Ikki Tarudai” was given to individuals living in Nishishiogo. Interestingly, after settling the festival expenses, any shortfall was apparently covered by the “Ikki Tarudai,” and this shortfall was deducted proportionally (at the same rate) before being distributed to the individuals. The Tarudai receipt ledger also recorded the addresses of the people who brought the donations, allowing us to know where the spectators came from.

Such large-scale village festivals incurred significant expenses for the local residents, but they also generated income other than donations. Items that could be procured within the village, such as stage materials and fuel, were purchased from residents, and households that lodged the actors were paid lodging fees. In this way, cash circulated within the region with a dazzling frequency unusual for everyday life, repeating expenditures and income many times in a short period. Items not available in the region were purchased from shops in the market town, reaching an amount of 177 yen. They also purchased large quantities of sake from multiple nearby breweries, showing that the village festival also served to vitalize the economy of the wider region, including the market towns.